David Nyheim, Chief Executive of ECAS and Managing Partner and Chairman of INCAS Consulting Ltd. (Malta).

Before going any further, there is an assumption that underpins this think-piece and which needs some elaboration. And that is a commonly shared belief that peace-making and peace-building are (among many) soft power instruments. “Soft power” is a term coined by Joseph Nye in the 1980s, which is “the ability of a country to persuade others to do what it wants without force or coercion”. Many who have read Nye’s 1990 book, “Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power” will recognise that the notion of “soft power” goes back by about 2400 years to Sun Tzu’s Art of War, making where we’re now at perhaps unsurprising. The evidence of how these particular instruments are part of soft power is seen in the foreign policy of several countries, including my own (Norway), where peace-making and peace-building are integral to the projection of foreign policy influence.

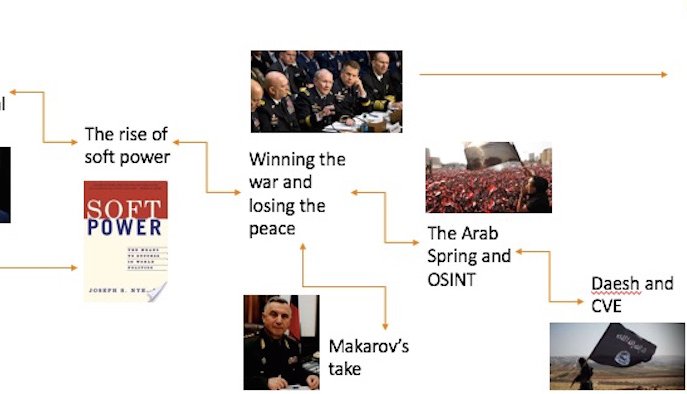

So what are the threads that have led to the entanglement of peace work into war-making?

The first thread, as mentioned, started with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The collapse of the Soviet Union and bipolar order saw a rise in civil conflicts across the world, including the Yugoslav wars (1991-2001), Somali war (1991-today), Georgian civil war (1991-1993), Rwandan civil war (1990-1994), and Chechen wars (1994-1996 and 1999-2009), to mention but a few. Intelligence services and military in the West and former Soviet republics realised that Cold War intelligence methods were inadequate to understand the dynamics of these conflicts. They became increasingly interested in (and wary of) the work of NGOs and universities involved in conflict early warning (part of the peace-building toolbox). Organisations such as Forum on Early Warning and Early Response (FEWER) were approached by intelligence agencies and had their activities monitored. There were several direct collaboration initiatives between intelligence and (particularly US) academia, including the State Failure Task Force (later Political Instability Task Force). This work was part of what led to the rise of Open Source Intelligence (the securitised twin of conflict early warning) (OSINT); an important tool in governmental efforts to monitor and analyse civil conflicts and a strategic addition (initially) to traditional intelligence gathering.

The second thread followed 9/11 and the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. While the initial toppling of the Taliban and defeat of Sadam Hussein’s military forces was swift, Allied forces quickly began to lose the peace. “Winning hearts and minds” became an important element in the battle for stability and Allied strategists turned to soft power for answers. A key soft power instrument became Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs). First deployed in Afghanistan in 2001 by the United States government, PRTs consist of military officers, diplomats, and reconstruction experts, who work to support reconstruction and stabilise in unstable areas. PRTs (also known as stabilisation teams) were later deployed to Iraq and carried out activities that are typically seen in peace-building and conflict-sensitive area-based development projects. The main difference being that PRT activities are carried out in conjunction with military forces and aligned to military objectives. A close association was formed, therefore, between developmental actors, peace-builders, and humanitarian workers – who were doing PRT work – and perceived (and actual) occupying forces in the eyes of the population and insurgents.

Some of the many challenges that emerge from the alignment of peace work to military objectives surfaced in a small perception survey conducted in 2012 byMona Chalabi, one of our talented ECAS Junior Associates at the time, across several governorates in Iraq. It was focused on ordinary Iraqi’s experiences of stabilisation. Among her findings was a perception by a majority of respondents that the greatest personal security threat during the occupation was posed by Allied forces, not by insurgents. That finding raises the question of how effective you can be in bringing sustainable peace and security to an area when you are seen as the principal threat; doing what some bluntly refer to “peace-building at gunpoint”. Related to this is a compromise on neutrality and the view of some insurgent groups and governments that organisations involved in peace-building and reconstruction are extensions of hostile soft power, and therefore legitimate military targets.

The third thread emerged with the colour revolutions in former Soviet republics and was strengthened by the Arab Spring. The significance of the Rose Revolution (Georgia, 2003), Orange Revolution (Ukraine, 2005), Pink Revolution (Kyrgyzstan, 2005), and social upheaval in several other former Soviet republics was of course not lost on Russia. Inspired, some will say by the work ofGene Sharpe on non-violent resistance, the colour revolutions prompted Russian military strategists to develop what is known as the Makarov Doctrine (see more about this below), and the Russian state to develop methods to manage “street politics” and tighten control of foreign funded civil society groups in Russia.

The Arab Spring (2010-2012) that came after the colour revolutions, saw the extensive use of social media to plan and execute demonstrations, thwart government counter-measures, and sway public opinion. It is seen by many in intelligence, diplomatic and military circles as the time when OSINT (conflict early warning’s securitised twin mentioned above) shifted from a strategic addition to traditional intelligence, to become an important tactical and operational tool. The events in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen showed that it had become possible to follow and support popular revolt in real time and by remote with tactically relevant information (e.g. how to counter the use of aerial surveillance of gatherings by burning tires). The hard power applications of soft power instruments came sharply into focus.

The final and most recent thread was the execution of Russian hybrid warfare strategy (the Makarov Doctrine) in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine. In February 2010, President Dmitry Medvedev signed what was later referred to as the Makarov Doctrine (named after former Chief of the General Staff Army-General Nikolai Makarov) otherwise known as Russia’s hybrid warfare (or non-linear warfare) strategy. Explained by Makarov’s successor, Valery Gerasimov, “a perfectly thriving state can, in a matter of months or even days, be transformed into an arena of fierce armed conflict, become a victim of foreign intervention, and sink into a web of chaos, humanitarian catastrophe, and civil war.” This, he said, could be done by combining “political, economic, informational, humanitarian”, and other soft power instruments with “the protest potential of the population”. Some will say that the strategy was executed by Russia in Crimea in 2014, leading to the annexation of the peninsula without any major military confrontation, and followed by the destabilisation of the Donbass region in eastern Ukraine.

Whereas Western soft power use in Afghanistan and Iraq was focused on winning the peace after military confrontation, Russian innovation was the deployment of soft power instruments from the very beginning and throughout a military campaign to great effect. And herein lies the fundamental challenge. These soft power instruments (political, economic, informational, humanitarian) now used for war-making are also at the core of the peace-making and peace-building toolbox.

So there. That is the story, then, of how the securitisation of peace happened, and how making and building of peace is increasingly becoming an instrument of war. For those involved in peace work, the key question is now how we do our work when our methods are also used to wage war?

So what’s the photograph? It is a snapshot of a slide from a presentation we recently gave to Chinese policy makers and think tanks on the securitisation of conflict prevention. It was the conclusion of a UK-China dialogue on conflict prevention, organised by Saferworld, and funded by the UK’s Department for International Development. It summarises the seven threads (yes – there are three more) that got making peace entangled with waging war. If you want to learn more about the photograph, the other three threads, or our work, just get in touch.